In the latest installment of our Privacy Protectors Spotlight series, we are excited to feature international privacy law expert Professor Daniel J. Solove!

Daniel J. Solove is the Eugene L. and Barbara A. Bernard Professor of Intellectual Property and Technology Law at George Washington University Law School. He serves as the co-director of the GW Center for Law & Technology and directs the Privacy and Technology Law Program. Beyond academia, he is the founder, President, and CEO of TeachPrivacy, an organization that provides privacy and data security training for businesses, schools, healthcare institutions, and other organizations.

A leading authority on privacy law, Solove has authored numerous books, including On Privacy and Technology (2025), Breached! (2022), Nothing to Hide (2011), Understanding Privacy (2008), The Future of Reputation (2007), and The Digital Person (2004). He has also co-authored several widely used textbooks on information privacy law with Paul M. Schwartz and has written a privacy-focused children’s book, The Eyemonger (2020). His scholarship has been published in top law journals, including Harvard Law Review, Yale Law Journal, Stanford Law Review, and Columbia Law Review, and his work has been cited extensively, including in U.S. Supreme Court decisions. He is the #1 most cited legal scholar born after 1970.

Solove has played a key role in shaping privacy law and policy, having testified before Congress, contributed to amicus briefs in major privacy cases, and served as a consultant or expert witness for high-profile litigation. He was a co-reporter for the American Law Institute’s Principles of the Law, Data Privacy and is a fellow at the Ponemon Institute and Yale Law School’s Information Society Project. He also sits on advisory boards for privacy-focused organizations such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) and the Future of Privacy Forum (FPF).

In addition to his academic and policy work, Solove is the founder and co-organizer of major privacy-focused conferences, including the Privacy + Security Forum, the Privacy Law Scholars Conference (PLSC), and the Higher Education Privacy Conference (HEPC). He has been widely quoted in media outlets such as The New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, and CNN. With over a million followers, he is recognized as a leading privacy thought leader on LinkedIn and shares insights through his Privacy+Security Blog.

A graduate of Yale Law School, Solove clerked for Judges Stanley Sporkin and Pamela Ann Rymer before working at Arnold & Porter and serving as a Senior Policy Advisor at Hogan Lovells LLP. Today, he continues to teach, write, and advocate for stronger privacy protections.

How Solove Became Interested in Privacy

Solove’s path to privacy law began at Yale Law School in 1996, where he took Professor Jack Balkin’s cyberspace-law course, the first time the course had been taught. At the time, very few internet-related legal cases had been decided, but the subject intrigued him. His early engagement with the internet in the mid-1990s, initially as a tool for tracking down physical books, played a role in shaping his perspective. One of the first books he purchased online was Alan Westin’s Privacy and Freedom (1967)—an early and influential text on privacy in the digital age.

After Balkin’s course, Solove intended to focus on cyberspace law, integrating a humanities perspective into legal and technology scholarship. He was influenced by the work of Richard Weisberg and James Boyd White, as well as Martha Nussbaum’s Poetic Justice (1995), which argued for the importance of literary imagination in legal reasoning. However, as he began researching and writing about privacy, the field proved far larger and more complex than he had expected.

In 1997, as he was finishing law school, Solove wrote his first law review article on privacy. At the time, privacy was a vastly underexplored topic in legal scholarship, and he initially thought he would write only a few pieces on the subject before moving on to other areas. Instead, he found himself going down a rabbit hole, realizing that privacy was a critical and evolving legal challenge that demanded deeper exploration. That realization set the stage for his career-long focus on privacy, law, and technology.

Solove’s Definition of Privacy and Myths About Privacy

Daniel Solove argues that privacy is often misunderstood, both by the public and by lawmakers. Instead of treating privacy as a single concept, he sees it as a multifaceted issue that involves control over personal information, the ability to limit surveillance, the power to correct inaccuracies, and the right to not be misrepresented or manipulated by data-driven decisions.

One of Solove’s key contributions is challenging the “secrecy paradigm”—the idea that privacy only matters if someone has something to hide. In Nothing to Hide, he dismantles this argument, showing that privacy is not just about secrecy but also about having control over how personal information is collected, used, and shared. Even if someone has nothing to hide, their personal data can still be used to profile them, restrict their opportunities, or make decisions about them without their knowledge.

Solove also debunks the “privacy vs. security” myth, which assumes that protecting privacy must come at the expense of security. He argues that privacy and security are not opposing forces; rather, good privacy protections often enhance security. For example, when organizations collect excessive amounts of personal data, they increase security risks by creating more opportunities for breaches and identity theft.

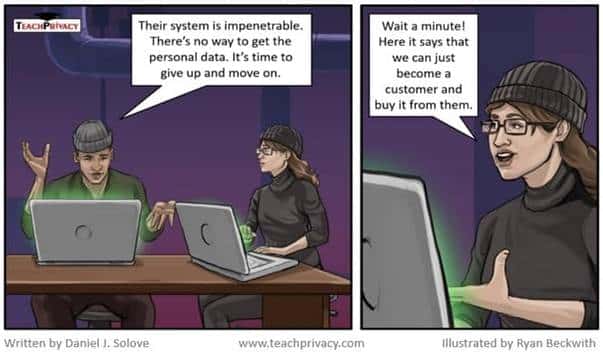

The Relationship Between Privacy and Data Security Cartoon

Another misconception Solove addresses is the “individual responsibility” myth—the belief that privacy is simply a matter of personal choice. He critiques the idea that people can fully protect themselves by adjusting their settings, reading privacy policies, or opting out of tracking. In reality, most data collection happens behind the scenes, without meaningful consent, and individuals have little ability to stop it. This is why Solove believes privacy should be treated as a structural issue, requiring legal protections rather than placing all the burden on individuals.

The Digital Person: Technology and Privacy in the Information Age (2004)

In his book The Digital Person, Daniel Solove examines how the rise of computerized record-keeping and data collection has transformed privacy, creating a world where vast amounts of personal information are continuously gathered, analyzed, and used by governments and businesses. He introduces the concept of the digital dossier—a detailed and ever-growing collection of data about individuals, compiled from transactions, online behavior, and government records. Unlike traditional surveillance, which requires active monitoring, digital dossiers develop passively, often without individuals realizing how much information is being amassed about them.

“Even if we’re not aware of it, the use of digital dossiers is shaping our lives. Companies use digital dossiers to determine how they do business with us; financial institutions use them to determine whether to give us credit; employers turn to them to examine our backgrounds when hiring; law enforcement officials draw on them to investigate us; and identity thieves tap into them to commit fraud.” (page 3)

One of Solove’s central arguments is that existing privacy laws fail to protect against the dangers posed by digital dossiers. Privacy law has historically focused on direct intrusions, such as government surveillance or wiretapping, but it does not adequately address data aggregation and secondary use—the way companies and agencies collect information for one purpose and then use it for another. He warns that data collection is no longer about individual transactions but about patterns, as organizations mine data to make predictions about people’s behaviors, risks, and even their potential future actions.

Solove critiques the assumption that people voluntarily give up their privacy when they engage in transactions or use online services. In reality, most individuals have little choice—they must participate in modern society, whether by using financial services, social media, or online commerce, all of which contribute to their digital dossiers. Moreover, these dossiers are often invisible and uncorrectable—individuals don’t know what information is being stored, cannot easily challenge inaccuracies, and have no control over how their data is used.

Another major theme in The Digital Person is the Kafkaesque nature of modern information systems. Drawing on Franz Kafka’s The Trial, Solove argues that the greatest privacy risks today do not come from a dystopian Big Brother-style government but from a bureaucratic, faceless system where decisions are made about individuals based on secretive and often inaccurate data.

“The problem is not simply a loss of control over personal information, nor is there a diabolical motive or plan for domination as with Big Brother. The problem is a bureaucratic process that is uncontrolled. These bureaucratic ways of using our information have palpable effects on our lives because people use our dossiers to make important decisions about us to which we are not always privy.” (page 9)

To address these issues, Solove advocates for a new legal framework for privacy. He calls for greater oversight of data collection practices, stricter limitations on how organizations use personal data, and stronger protections for individuals to access and correct their records.

At the time of its publication in 2004, The Digital Person was a groundbreaking work. Many of the problems Solove identified—opaque data broker practices, lack of legal protections, and the dangers of uncontrolled data aggregation—have only intensified.

Solove’s Taxonomy of Privacy

In his 2006 paper “A Taxonomy of Privacy“, Daniel Solove introduced a novel framework for categorizing privacy problems, which has since been widely cited in legal scholarship, court rulings, and policy discussions. He later expanded on this taxonomy in his 2008 book Understanding Privacy, where he provided a more detailed analysis of how privacy violations occur and why traditional legal approaches often fail to address them.

Solove’s taxonomy organizes privacy issues into four main categories:

- Information Collection – Unwanted surveillance, data gathering, and other forms of intrusive monitoring.

- Information Processing – Data aggregation, storage, and use that may lead to profiling, discrimination, or secondary use.

- Information Dissemination – Unauthorized data sharing, leaks, identity theft, and reputational harm.

- Invasions – Direct interferences with personal autonomy, such as intrusions into private life or excessive government and corporate control.

Unlike older privacy models that focus mainly on secrecy or personal control, Solove’s approach highlights the structural and systemic risks posed by modern data collection. This taxonomy has provided policymakers and courts with a clearer way to identify privacy harms and has shaped discussions on data protection laws, privacy regulations, and corporate compliance policies.

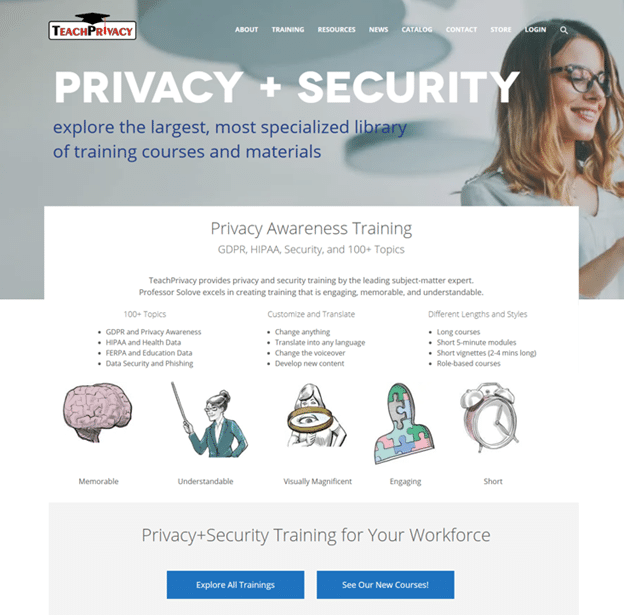

TeachPrivacy: Privacy and Security Training

As part of his efforts to protect privacy, in 2010, Daniel Solove founded TeachPrivacy, a company dedicated to providing engaging and effective privacy and data security training for organizations across various industries. TeachPrivacy offers computer-based training modules covering a wide range of topics, including CCPA, GDPR, HIPAA, FERPA, GLBA, TCPA, phishing, social engineering, and other critical privacy and cybersecurity issues. The courses incorporate videos, quizzes, and interactive elements to ensure employees understand privacy and security risks and how to mitigate them.

What sets TeachPrivacy apart is Solove’s hands-on approach. Unlike many training programs developed by general instructional designers, TeachPrivacy courses are crafted by a subject-matter expert with decades of experience in privacy law. Solove personally oversees the creation of all training programs, leveraging his deep knowledge of legal frameworks, regulatory enforcement trends, and real-world privacy challenges. His relationships with privacy and security professionals also help refine the material to ensure it aligns with industry best practices.

TeachPrivacy has provided training for hundreds of organizations, including many Fortune 500 and Fortune 1000 companies, as well as government entities, hospitals, technology firms, financial institutions, and higher education institutions. The company’s approach goes beyond just offering generic online courses—it works closely with clients to customize content, provide additional resources, and design training programs that fit their specific needs.

Solove’s philosophy on training is rooted in effective teaching principles: privacy awareness should be engaging, memorable, and accessible. He emphasizes the use of storytelling, real-world examples, and interactivity to make complex privacy laws and security practices understandable. In his own words, “People will not learn unless they care. To make people care, a teacher must be engaging and have genuine passion for the subject.”

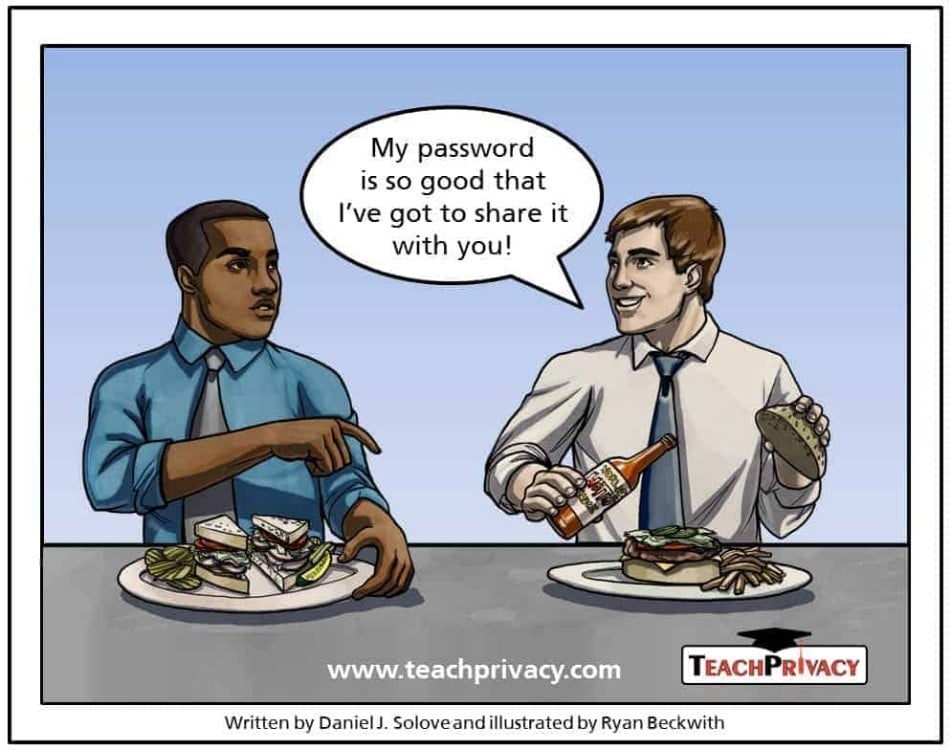

As part of his training programs, Solove uses humor to make privacy and security issues more engaging.

Through TeachPrivacy, he creates cartoons that highlight common privacy pitfalls, regulatory challenges, and the absurdities of modern data collection. These cartoons have been widely shared in privacy and security circles, offering a lighthearted yet insightful take on serious issues.

Through TeachPrivacy, Solove has created one of the most respected privacy and security training platforms, equipping organizations with the knowledge to better protect sensitive data and comply with evolving privacy regulations.

The Eyemonger (2020)

In The Eyemonger, Daniel Solove brings his expertise in privacy law into children’s literature, using an imaginative and slightly eerie tale to introduce young readers to the dangers of surveillance and the value of privacy.

The story follows a mysterious, eyeball-covered figure called The Eyemonger, who arrives in a small city and convinces its residents to let him take over their security. With his many eyes and an army of floating eyeballs, he promises to prevent all wrongdoing and make sure everyone gets along. The townspeople enthusiastically accept his offer, but as his surveillance expands, the weight of constant monitoring begins to stifle creativity and freedom.

It is Griffin, a young artist, who finally refuses to comply, resisting the Eyemonger’s “nothing to hide, nothing to fear” philosophy. The Eyemonger, in turn, comes to understand that constant surveillance does not create harmony but instead crushes inspiration and self-expression.

With rhyming text and vividly detailed illustrations, The Eyemonger is a thought-provoking and visually engaging story about privacy, consent, and the impact of surveillance on creativity.

By presenting these complex issues in a storytelling format, Solove makes privacy relatable and understandable to a younger audience—an audience that will inevitably grow up navigating an era of data collection, social media, and online tracking.

Breached! Why Data Security Law Fails and How to Improve It by Daniel J. Solove & Woodrow Hartzog (2022)

In Breached!, Professors Solove and Woodrow Hartzog argue that current data security laws are failing because they focus too much on breaches themselves rather than the broader systemic issues that make breaches inevitable. They emphasize that existing legal frameworks punish organizations after a breach has occurred but do little to prevent breaches in the first place. The book proposes a holistic approach to data security law that considers human behavior, systemic failures, and the broader data ecosystem, rather than just targeting companies that experience breaches.

The book criticizes the reactive nature of laws, which prioritize breach notification and post-incident penalties rather than proactive risk reduction. The authors argue that designing security around human behavior, rather than expecting people to change, is key to improving outcomes. They examine real-world breaches, such as the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) hack, to show how poor privacy practices make security failures more catastrophic, and that privacy and security go hand-in-hand.

“Privacy is a key and underappreciated aspect of data security. Lawmakers and industry should break down the regulatory and organizational silos that keep them apart and strengthen our privacy rules as one way to enhance data security and mitigate breaches.” (page 10)

To move beyond the reactive approach that dominates current data security law, Solove and Hartzog propose a new framework that prioritizes prevention, accountability, and human-centered security design. They outline four key areas where the law must improve:

- Holding All Actors Accountable – Instead of focusing solely on breached companies, security regulations should also place responsibility on software vendors and device manufacturers for the insecure systems they create. Many security failures originate not from the breached company itself but from poorly designed technology and weak default security settings.

- Prioritizing Prevention Over Reaction – Laws should shift from post-breach penalties to proactive security measures, such as data minimization and privacy-by-design, to reduce breach impact before it happens.

- Designing for Humans, Not Just Systems – Security frameworks should acknowledge that human error is inevitable and build safeguards accordingly. Instead of relying on complex passwords that users often forget, for example, multi-factor authentication and password managers offer stronger security with less risk.

- Strengthening the Relationship Between Privacy and Security – Privacy is often treated as separate from security, but Solove and Hartzog argue that stronger privacy protections reduce security risks. Laws should limit excessive data retention, as large datasets increase breach risks and harm individuals when exposed.

By addressing these systemic failures, Breached! advocates for a fundamental shift in data security law, one that focuses on preventing breaches rather than just cleaning up the damage afterward.

Privacy Harms by Danielle Keats Citron and Daniel J. Solove (2022)

In “Privacy Harms“, Professors Solove and Danielle Keats Citron argue that privacy violations frequently go unaddressed because courts and laws fail to recognize the full extent of harm caused by the misuse of personal data. Courts often dismiss privacy harms as intangible or speculative, requiring proof of direct financial or physical damage. However, many privacy harms manifest as psychological distress, reputational damage, and loss of autonomy—forms of harm that the legal system does not consistently acknowledge.

The authors also emphasize that privacy violations are not isolated incidents; rather, they accumulate and create widespread societal consequences. Small, individual harms such as frustration, anxiety, and inconvenience may seem insignificant in isolation, but when experienced at scale, they lead to substantial collective harm.

Solove and Citron highlight how data brokers amass extensive personal data from various sources without individuals’ knowledge or consent, making it difficult for people to assess or challenge how their information is being used. Seemingly minor data points—such as location history or browsing habits—are aggregated to form detailed profiles that enable discrimination, manipulation, and fraud.

This kind of surveillance can also have a ‘chilling effect’. As the authors state, “chilling effects have an impact on individual speakers and society at large as they reduce the range of viewpoints expressed and the nature of expression that is shared. Monitoring of communications can make people less likely to engage in certain conversations, express certain views, or share personal information” (page 62).

The authors argue that the widespread dissemination of personal information, which individuals cannot predict or control, constitutes a significant societal harm.

To address these challenges, Solove and Citron propose reforms that would realign privacy enforcement with its intended goals. They advocate for recognizing psychological and reputational harm as legally cognizable, holding data brokers accountable for the harm caused by their business practices, and strengthening consumer rights over personal data. Courts should expand their definitions of harm to include emotional distress and loss of autonomy, while companies profiting from personal data should be legally responsible for preventing its misuse. The authors argue that privacy regulations should shift from being reactive—addressing harm only after it occurs—to proactive enforcement that prevents violations before they happen. Without such reforms, privacy law will continue to fail at protecting individuals and society from the growing harms of unchecked data exploitation.

Artificial Intelligence and Privacy (2025)

In his recent article “Artificial Intelligence and Privacy,” Professor Solove explores how AI affects privacy, arguing that while AI introduces new challenges, it primarily amplifies existing privacy problems rather than creating entirely new ones. He challenges the idea that AI requires a completely different approach to privacy regulation, instead advocating for strengthening privacy laws to address the issues AI magnifies.

“AI alters the way decisions are made, facilitating predictions about the future that can affect people’s treatment and opportunities. These predictions raise concerns about human agency and fairness.

AI is also used in non-predictive decisions about people, transforming how bias affects decisions. AI decision-making involves automation, and there are problems caused by automated processes that the law has thus far struggled to address. AI also enables unprecedented data analysis, which can greatly enhance surveillance and identification. Privacy law has long inadequately addressed the problems caused by surveillance and identification. AI threatens to take these problems to new heights and add troublesome new dimensions.” (page 18)

One of Solove’s main points is that AI complicates privacy at two key stages—when it collects data (inputs) and when it generates new information (outputs). AI systems are often trained on massive amounts of personal data, gathered through methods like web scraping, surveillance, and data aggregation. Many people never realize their data is being used this way, making traditional privacy protections—like consent—largely ineffective. On the output side, AI doesn’t just analyze existing data; it creates new information, making predictions about people’s behavior, preferences, and even their identities. These AI-generated insights can lead to unfair profiling, discrimination, and automated decision-making that affects people’s lives without their knowledge or consent.

Despite AI’s growing role in society, privacy laws have not kept up. Solove critiques current regulations for placing too much responsibility on individuals to protect their own privacy. Laws that rely on notice and consent—where users agree to privacy policies—are largely meaningless in an AI-driven world where data is collected behind the scenes and used in ways people don’t anticipate. Instead of focusing on individual responsibility, Solove argues that privacy laws need to take a more structural approach, holding companies accountable for how they collect and use personal data.

Ultimately, Solove makes the case that AI isn’t introducing a brand-new privacy crisis—it’s just making long-standing problems bigger and more urgent. He believes that stronger, well-enforced privacy laws would already address many of AI’s risks—such as mass data collection, biased decision-making, and hidden surveillance.

Privacy in Authoritarian Times (2025)

In another recent article, “Privacy in Authoritarian Times,” Solove explores how privacy functions as a fundamental safeguard against authoritarian overreach. He argues that both government surveillance and the widespread data collection practices of private companies—what Shoshana Zuboff termed surveillance capitalism—work in tandem to expand authoritarian power.

“Authoritarian governments seek to control people by invading their private lives. They envelop people in surveillance to ensure that people are obedient. They ferret out dissenting thought to be attacked – with threats, ostracism, blacklisting, pretextual law enforcement, and outright criminal penalties. They seek to control people’s bodies and minds. They use personal data to manipulate, blackmail, apprehend, or punish people. Authoritarian power is greatly enhanced in today’s era of pervasive surveillance and relentless data collection.” (page 4)

Solove outlines how modern authoritarianism does not necessarily rely on extralegal force; instead, it often operates within legal frameworks, using laws as tools of repression.

A major legal flaw, according to Solove, is the third-party doctrine, which allows the government to access personal data stored by companies without a warrant. This means that data collected by social media platforms, phone companies, and online services is readily available for government use.

“The Fourth Amendment offers little to no protection for much of our personal data in the digital age, largely due to the third-party doctrine.” (page 4)

Additionally, Solove warns that companies frequently comply with government demands for data, rather than resisting them.

“When the government demands access to personal data or the use of corporate technologies, will companies resist? History suggests the answer is likely no.” (page 5)

He cites historical and modern examples where corporations handed over vast amounts of data to authoritarian governments, highlighting this as a significant danger of unchecked corporate data collection.

A key argument of the article is that privacy protections must be significantly strengthened, not only by reforming Fourth Amendment jurisprudence but also by regulating the private sector’s role in mass data collection. Solove emphasizes that government surveillance and corporate surveillance are two sides of the same coin, and tackling authoritarian privacy intrusions requires addressing both.

To combat these threats, Solove proposes comprehensive regulatory reforms, including:

- Overturning the Third-Party Doctrine, which currently allows governments to access vast amounts of personal data stored by companies.

- Implementing data minimization laws to limit the amount of personal data that companies collect and retain.

- Strengthening legal protections against dragnet surveillance, ensuring that government monitoring is subject to stricter oversight.

- Holding private companies accountable for enabling authoritarian surveillance, whether through data sales, AI-driven profiling, or compliance with oppressive government demands.

Solove warns that without meaningful privacy protections, societies risk enabling authoritarianism not just through state power but also through corporate complicity. He argues that a legal and regulatory framework strong enough to withstand authoritarian pressures must be built proactively, rather than in response to crises.

This article presents a compelling case for why privacy should be seen as a pillar of democratic resilience, rather than merely a personal preference. Solove contends that the erosion of privacy is not just a matter of individual rights but a broader threat to civil liberties, free thought, and resistance against authoritarianism.

On Privacy and Technology (2025)

Daniel Solove’s latest book, On Privacy and Technology, is a culmination of his 25 years of thinking about privacy. It brings together his insights into how privacy should be defined, how technology has transformed it, and why existing privacy laws have largely failed. While the book expands on many of the themes from Solove’s previous works, it brings them together in a comprehensive way and further develops his critique of structural flaws in privacy law and the role of technology in shaping human behavior.

One of Solove’s most important arguments in On Privacy and Technology is that privacy laws are failing because they are designed for compliance rather than real protection. Too often, companies approach privacy as a checklist—meeting minimum legal requirements rather than making ethical decisions about data collection and usage. Solove believes that privacy law should shift from rigid, rule-based compliance models to more adaptable, responsibility-driven approaches.

Laws should not just regulate what data can be collected, but also impose limits on how companies can use and monetize personal information.

Solove also notes how many companies don’t need to force users to share data; they design services that make people want to share. From social media to personalized advertising, people are nudged toward revealing more about themselves than they might otherwise choose. Solove argues that privacy law must account for this behavioral influence, recognizing that data collection is not always truly voluntary.

Another key issue Solove tackles is the failure of privacy laws to keep up with technological change. Many laws, like the U.S. Electronic Communications Privacy Act, were written for a completely different era of technology, making them ill-suited for today’s digital world. But even newer privacy laws often struggle because they rely on outdated models of consent and individual control, rather than addressing systemic issues in how organizations manage and exploit data. Solove highlights the Video Privacy Protection Act as a rare example of flexible, forward-thinking privacy law—one designed to apply broadly to emerging technologies, rather than being limited to a specific industry or platform.

In the final pages of the book, Solove reflects on the future of privacy, acknowledging that while privacy will always be under threat, it is not beyond saving. He pushes back against both privacy defeatism (the idea that privacy is dead) and technological solutionism (the belief that privacy will be solved through better technology). Instead, he sees privacy as an ongoing project, requiring constant effort, vigilance, and advocacy.

“Privacy isn’t yet dead . . . but it isn’t secure. We can’t escape from the worry that privacy may be dying, nor should we. As technology evolves, privacy will always be in danger. We must constantly work to keep it alive, like emergency room doctors desperately trying to save a critical patient. We can never rest. Protecting privacy is destined to be an ongoing project, not a problem to be solved. Many of the challenges technology poses for privacy weren’t created by technology—these problems already existed. But technology exacerbates and amplifies; it speeds things up and makes things bigger. We must address the threats it now presents and we must keep at it, without allowing either fear or worship of technology to get in the way.” (page 109)

Daniel Solove and Privacy Protection

Over the course of his career, Daniel Solove has been an indispensable figure in the fight for privacy. Through his widely cited legal scholarship, he has introduced new ways of understanding privacy and provided paths forward for courts, regulators, and policymakers to classify, prevent, and address privacy violations more effectively.

As someone who has dedicated himself to privacy education, Solove has helped countless professionals and businesses strengthen their privacy and data security practices. He has also extended his educational efforts to the general public, writing books that explain privacy issues in ways that resonate with a broad audience—including his children’s book, The Eyemonger.

Through his scholarship, policy advocacy, and educational initiatives, Daniel Solove continues to shape the way privacy is understood, how it is threatened, why it must be protected, and how legal and policy frameworks must evolve to keep pace with emerging threats. His contributions to privacy are invaluable.

At Optery, we are greatly inspired by Professor Solove’s work and are happy to spotlight him for his outstanding contributions to privacy protection.

Join us in recognizing Daniel Solove’s important work. You can check out his publications here: Publications – Daniel J. Solove and receive weekly information about his training, writings, events, and resources by subscribing to his newsletter here: Privacy Newsletter by Daniel J. Solove | TeachPrivacy

You can also follow him here:

- Professor Solove’s LinkedIn Influencer blog

- Professor Solove’s Twitter Feed

- Professor Solove’s Newsletter

Join one or more of Professor Solove’s LinkedIn Discussion Groups here:

Stay tuned for more features in our Privacy Protectors Spotlight series and follow Optery’s blog for further insights on safeguarding your personal information.